De la educación a la cultura / From education to culture

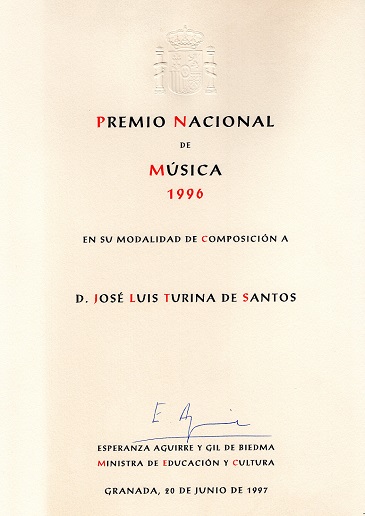

Words of thanks read on the occasion of the delivery of the National Dance and Music Awards 1996 (Grenada, June 20, 1997)Her Excellency Mrs. Minister; Most Excellent and Most Illustrious Authorities; Ladies and Gentlemen:

In addition to the magnificent occasion that being able to express my feelings publicly constitutes in itself, I have the immense honor of representing two distinguished figures of Spanish music and dance, as they have been able to raise the level of the artistic field that they received from its predecessors quite a few points beyond where they left off. If in the future, the name of Teresa Berganza will always be associated with the best imaginable tasks in terms of singing, that of Cesc Gelabert will do so in a magical pas de deux with his rich and suggestive choreographies at the service of contemporary dance. As a simple spectator and admirer of your art, from here I would also like to send you my warmest and most affectionate congratulations for this Award, and make public my envy -not out of healthy, less envy- for those who have known how to make their voice and his body suitable vehicles of a lofty artistic expression.

Those of us who dedicate ourselves to any of the arts that have time as a raw material have learned, throughout our activity, that every event, no matter how small, that occurs during the course of a work will have its consequence a little later, if it is not in itself a consequence of something that happened a little earlier. A superb high C, a magnificent pirouette or a spectacular orchestral chord are meaningless outside the context that precedes and follows them.

Our works have taught us to live artistically with one foot in the past and the other in the future, in a continuous present that we are obliged to dominate, if we want not to lose control over the work, our own or another's, that we have in hand.

That temporal ubiquity in which we develop makes us naively believe, in a certain way, different; and, if in fact we are, it is because we have learned to obtain the maximum performance, for exclusively artistic purposes, from a primordial instinct of the human being, which is none other than that of forecasting the future based on past experience. With total unconsciousness, but with the conviction of believing ourselves in possession of an unquestionable truth, in each new work we launch ourselves suicidally into the void in pursuit of that own ideal of perfection that we call Beauty, to which we are getting closer, but to which we never quite reached. After each work, always unsuccessful in that sense, another one has to come that surpasses it and places us a little closer to what we are looking for, because every time we think we have advanced, we immediately notice that the objective has mocked us, standing a little further than we thought: the search has also made us demanding.

Permanent creation throughout a lifetime does not have its reason for being in the supposed advantages of quantity over quality. Quite the contrary, the only thing that justifies it is its therapeutic nature in the face of the continuous dissatisfaction caused by never being able to achieve the perfection we seek. The process is so painful that those of us who live immersed in it need external stimuli more than anyone to encourage our work and help us start each work as if it were the first. In short, it is not enough for us to create new works: we also need to reach those around us with them, make them share our concerns and infect them with our enthusiasm for the idea of Beauty that we have been forging and that obsesses us so much.

Since Kant we know that the participation of others, passive and active at the same time, in the artistic work is only possible through taste, as well as that it must be permanently cultivated, with the double purpose of being able to extract the maximum benefit from its expansion, and to avoid its stagnation and consequent reduction to a mere and simple juxtaposition of prejudices. The way for all this is none other than knowledge, which, of course, can only be achieved through education.

In this retrograde relationship of concatenations that I have tried to string together, education and culture are but the extremes of an uninterrupted process that, however, can be conceptually fragmented into as many subdivisions as desired. In any case, education will always be in the past with respect to the maturity that will allow the exercise and enjoyment of culture, while this, as the only possible breeding ground for the constant spiritual improvement of the human being, will suppose the desirable future that will serve as a reference for the development of the extremely important initial training phase.

Like Music and Dance, twinned since their origins and, as could not be less, in this act, education and culture are like the heads and tails of a single coin, whose balance must be guaranteed through a continuous and rigorous control of the specific weight of both, so that the progress of one of them does not occur at the expense of the development of the other. For this reason, those of us who have made culture in general, and art in particular, the axis of our lives, must feel equally committed to both, since one is meaningless without the other, just as it happens to them. to our high Cs, our pirouettes or our orchestral chords if we dispossess them of their context.

In my family we have been alternating painters and musicians for four -almost five- generations. Perhaps that is why we have developed an enriching perceptive synthesis of the visual and sound aspects of the world around us. Many years before I met her, when I was still a child and finding myself, therefore, in the formative, artistic and human phase, my father instilled in me a special interest in the Alhambra, when he told me about the impression that his first visit to such an admirable site produced on him. Two things, of the many that he told me then, remained etched forever in my memory: one, that for him, a painter, the most spectacular thing about the view of Granada from the Alhambra was how the noises of the city rose up there "made music"; the other, the constant sensation of being in a place designed and realized, in all its aspects, to the measure of man. This last one was a magnificent first lesson of artistic proportions that I will never forget, and whose content I have tried to apply both to my music and to my relative vision of the world.

These words of thanks, which began stubbornly entangling themselves in the past and the future and have ended up becoming a reflection on the human dimensions with which to measure everything around us, must end, as the canons of classical composition dictate, with a synthesis of both thematic ideas.

By virtue of the temporal ubiquity that our artistic experience has given us, we have learned to draw ethical conclusions from what were apparently nothing more than aesthetic premises. We, the recent winners, know that this Award, which from now on we will display with pride, is both a recognition of the work carried out in the past, and a point of no return with which our professional future is indelibly marked, a level below which we will be, if incurred, duly claimed. We receive it, therefore, with the natural joy that its concession supposes, but also with the inevitable seriousness that implies the awareness of the difficulties that it obliges.

On behalf of Teresa Berganza, Cesc Gelabert and myself, thank you very much.

Information and commentary by Enrique Franco on the award of the 1996 National Prize

(El País, November 13, 1996)